GP2 in review - Hamilton at a canter......

If nobody quite knew what to expect in the first season of GP2 last year, then this time our hopes were high. Close fought racing between almost F1-quick single seaters with no electronic trickery or driving aids and most of the best aspiring young would-be F1 drivers at the wheel. With slick tyres this year, they edged still closer to the back of the F1 grid in performance terms - on occasion they might have been in a position to give at least the earliest version of the Aguri F1 car a fright in lap speed terms. In other words - more often than not the most interesting part of the Grand Prix weekend. I think its fair to say that GP2 entirely lived up to these elevated expectations this year.

At the start of the year, I predicted that the title battle would be fought between between Premat, Lapierre, Carroll and Piquet. Which shows how much I know. In my defence, I can only point out that, of the newcomers, I did single out Glock and Hamilton as the series debutants most likely to upset the applecart. Certainly I didn't expect Hamilton to take the championship by the kind of margin that he eventually did.

If the championsip battle was not as close fought as that between Kovalainen and Rosberg last year, the same could not be said of the individual races, some of which were very hotly contested indeed. The battle between Jose Maria Lopez and Timo Glock in the sprint race at Hockenheim stands out in particular, while the last lap of the feature race at Barcelona, where ART team mates Premat and Hamilton fought it out was a graphic illustration of how close it sometimes got.

In all there were 9 different winners in the 22 races this year. For sure, the feature/sprint race split, with the latter being run with semi-reversed grids, probably inflated this number a little (neither Andreas Zuber nor Michael Ammermuller ever really looked like winning a feature race) but there were still 6 different winners in the 11 feature races - not a bad total when compared with F1, or especially with this year's world rally championship.

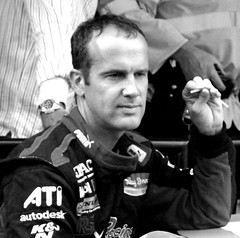

With 5 wins, three of them in feature races, and a further 9 podium finishes, Hamilton was clearly the dominant force this year, and the way he dominated his second-year team mate, Alexandre Premat (who, after all, was not really any slower than Nico Rosberg last year, merely a little less consistent) indicates that he is something really rather special indeed. Whether or not he gets the Mclaren seat alongside Alonso next year, it seems pretty clear that this is a young man who is going places.

To my mind, the numbers are about right in placing Nelson Angelo Piquet best of the rest. Like his father, he seemed happiest when out in front, and never really seemed to have the same racer's instinct as Hamilton. Neither was he as consistently quick, but on the other hand, it was hard to evaluate the competitiveness of his team (Xandi Negrao never really figured in the other Piquet Sports car) and he perhaps didn't have as good a car as ART were able to provide Hamilton with. He also showed impressive speed in the wet at Hungary, winning both races, and wet weather speed is always a sign that there is something special about a driver. He deserves his Renault testing role, now that Heikki Kovalainen has been promoted to the race team for 2007. Whether he has the mental toughness and racer's instinct to be a really first rate F1 driver, on the other hand, remains to be seen.

There remains the tantalising thought that had Giorgio Pantano done all the races, or had Timo Glock started the season with ISport, rather than with BCN, with whom he never really seemed to gel, one of these two ex-Jordan F1 drivers might have given Piquet and Hamilton a serious run for their money. The numbers suggest they probably would not quite have been able to, but Glock, in particular, looked more than a match for anyone in the second half of the season. Certainly it is a mystery why he was quite so slow in the BCN Competition car, and does beg questions about the degree to which team, rather than driver ability, plays a part in a series where the cars are supposed to be identical.

Equally intriguing were the sheer number of occasional one-off outstanding performances that were witnessed over the course of the year. Franck Perera, for instance, might not generally have made much of an impression, scoring just 8 points all season - but he got all 8 of those at Monaco, where he started and finished 2nd, behind Hamilton. There was another front row start for him at the Nurburgring - just enough perhaps, to suggest that the Toyota junior driver might make rather more of an impression if he gets another run next year - but still very much against the run of form. On other occasions, Hiroki Yoshimoto, Tristan Gommendy, Adrian Valles and DPR boys Olivier Pla and Clivio Piccione all showed flashes of real front running pace (Gommendy's front row start at Valencia, Valles' podium at the same, Yoshimoto's performances at Imola and the Nurburgring and the DPR drivers' performance at Monaco. None though, were able to threaten the front runners on anything like a regular basis - though whether this boiled down to inexperience, the limitations of their team, or their own foibles as drivers was very hard to tell. Yoshimoto, though, does look a rather more sensible bet for a Super Aguri drive than either Yamamoto or Ide did.

There were a few notable disappointments this year as well. Arden failed to recapture the form that took them to so many F3000 titles, and perhaps have lost the momentum they had before team owner Christian Horner took up Dietrich Mateschitz's offer to run Red Bull Racing. Of course, it might be the fault of the drivers. I, for one, expected Nicolas Lapierre and fellow Frenchman Alexandre Premat to figure a little more strongly after their dominant winter double act over in A1GP, but Premat was rarely close to his team mate Hamilton, while Lapierre came no closer to actually winning a race than he did last year. He was at least a little closer to the front than he had been last year, though an injury at Monaco put paid to any kind of a serious challenge.

Another man to struggle despite high pre-season hopes was Racing Engineering No1 driver Adam Carroll. In race trim he was as aggressive as ever, but he was often off the pace in qualifying, seemed to be harder on his tyres than just about anyone else in the field (for which he often paid a heavy price in the longer feature races) and, in the first part of the season at least, simply made too many mistakes. Whether the problem lay with Carroll, or Racing Engineering (whose other driver, Jose Villa looked utterly lost after being talked about as the 'new Fernando Alonso' in F3 the year before) was hard to tell. Perhaps it was a combination of the two - Carroll has always struck me as being a 'seat of the pants' kind of racer, and he might have suffered for not having an experienced team mate to help get car set up pointing in the right direction. Champ Cars seems the obvious place for him, if you as me.

Of the rest, Ferdinando Monfardini occasionally impressed, Lucas DiGrassi had a reasonable mid-season run, Felix Porteiro looked like a driver who might shine given a little more experience, and that was about it. Jason Tahinci, Fairuz Fauzy, Sergio Hernandez and Vitaly Petrov, in particular, seemed to represent a waste of a good cockpit.

So, not a bad sophomore year, all in all - the series did a pretty good job of establishing itself as not only the most important European single seater championship outside F1, but as being at least as competitive and suffused with talent as the IRL and Champ Car series. With the big names once again moving on to bigger and supposedly better things, lets hope that 2007 proves as exciting.

At the start of the year, I predicted that the title battle would be fought between between Premat, Lapierre, Carroll and Piquet. Which shows how much I know. In my defence, I can only point out that, of the newcomers, I did single out Glock and Hamilton as the series debutants most likely to upset the applecart. Certainly I didn't expect Hamilton to take the championship by the kind of margin that he eventually did.

If the championsip battle was not as close fought as that between Kovalainen and Rosberg last year, the same could not be said of the individual races, some of which were very hotly contested indeed. The battle between Jose Maria Lopez and Timo Glock in the sprint race at Hockenheim stands out in particular, while the last lap of the feature race at Barcelona, where ART team mates Premat and Hamilton fought it out was a graphic illustration of how close it sometimes got.

In all there were 9 different winners in the 22 races this year. For sure, the feature/sprint race split, with the latter being run with semi-reversed grids, probably inflated this number a little (neither Andreas Zuber nor Michael Ammermuller ever really looked like winning a feature race) but there were still 6 different winners in the 11 feature races - not a bad total when compared with F1, or especially with this year's world rally championship.

With 5 wins, three of them in feature races, and a further 9 podium finishes, Hamilton was clearly the dominant force this year, and the way he dominated his second-year team mate, Alexandre Premat (who, after all, was not really any slower than Nico Rosberg last year, merely a little less consistent) indicates that he is something really rather special indeed. Whether or not he gets the Mclaren seat alongside Alonso next year, it seems pretty clear that this is a young man who is going places.

To my mind, the numbers are about right in placing Nelson Angelo Piquet best of the rest. Like his father, he seemed happiest when out in front, and never really seemed to have the same racer's instinct as Hamilton. Neither was he as consistently quick, but on the other hand, it was hard to evaluate the competitiveness of his team (Xandi Negrao never really figured in the other Piquet Sports car) and he perhaps didn't have as good a car as ART were able to provide Hamilton with. He also showed impressive speed in the wet at Hungary, winning both races, and wet weather speed is always a sign that there is something special about a driver. He deserves his Renault testing role, now that Heikki Kovalainen has been promoted to the race team for 2007. Whether he has the mental toughness and racer's instinct to be a really first rate F1 driver, on the other hand, remains to be seen.

There remains the tantalising thought that had Giorgio Pantano done all the races, or had Timo Glock started the season with ISport, rather than with BCN, with whom he never really seemed to gel, one of these two ex-Jordan F1 drivers might have given Piquet and Hamilton a serious run for their money. The numbers suggest they probably would not quite have been able to, but Glock, in particular, looked more than a match for anyone in the second half of the season. Certainly it is a mystery why he was quite so slow in the BCN Competition car, and does beg questions about the degree to which team, rather than driver ability, plays a part in a series where the cars are supposed to be identical.

Equally intriguing were the sheer number of occasional one-off outstanding performances that were witnessed over the course of the year. Franck Perera, for instance, might not generally have made much of an impression, scoring just 8 points all season - but he got all 8 of those at Monaco, where he started and finished 2nd, behind Hamilton. There was another front row start for him at the Nurburgring - just enough perhaps, to suggest that the Toyota junior driver might make rather more of an impression if he gets another run next year - but still very much against the run of form. On other occasions, Hiroki Yoshimoto, Tristan Gommendy, Adrian Valles and DPR boys Olivier Pla and Clivio Piccione all showed flashes of real front running pace (Gommendy's front row start at Valencia, Valles' podium at the same, Yoshimoto's performances at Imola and the Nurburgring and the DPR drivers' performance at Monaco. None though, were able to threaten the front runners on anything like a regular basis - though whether this boiled down to inexperience, the limitations of their team, or their own foibles as drivers was very hard to tell. Yoshimoto, though, does look a rather more sensible bet for a Super Aguri drive than either Yamamoto or Ide did.

There were a few notable disappointments this year as well. Arden failed to recapture the form that took them to so many F3000 titles, and perhaps have lost the momentum they had before team owner Christian Horner took up Dietrich Mateschitz's offer to run Red Bull Racing. Of course, it might be the fault of the drivers. I, for one, expected Nicolas Lapierre and fellow Frenchman Alexandre Premat to figure a little more strongly after their dominant winter double act over in A1GP, but Premat was rarely close to his team mate Hamilton, while Lapierre came no closer to actually winning a race than he did last year. He was at least a little closer to the front than he had been last year, though an injury at Monaco put paid to any kind of a serious challenge.

Another man to struggle despite high pre-season hopes was Racing Engineering No1 driver Adam Carroll. In race trim he was as aggressive as ever, but he was often off the pace in qualifying, seemed to be harder on his tyres than just about anyone else in the field (for which he often paid a heavy price in the longer feature races) and, in the first part of the season at least, simply made too many mistakes. Whether the problem lay with Carroll, or Racing Engineering (whose other driver, Jose Villa looked utterly lost after being talked about as the 'new Fernando Alonso' in F3 the year before) was hard to tell. Perhaps it was a combination of the two - Carroll has always struck me as being a 'seat of the pants' kind of racer, and he might have suffered for not having an experienced team mate to help get car set up pointing in the right direction. Champ Cars seems the obvious place for him, if you as me.

Of the rest, Ferdinando Monfardini occasionally impressed, Lucas DiGrassi had a reasonable mid-season run, Felix Porteiro looked like a driver who might shine given a little more experience, and that was about it. Jason Tahinci, Fairuz Fauzy, Sergio Hernandez and Vitaly Petrov, in particular, seemed to represent a waste of a good cockpit.

So, not a bad sophomore year, all in all - the series did a pretty good job of establishing itself as not only the most important European single seater championship outside F1, but as being at least as competitive and suffused with talent as the IRL and Champ Car series. With the big names once again moving on to bigger and supposedly better things, lets hope that 2007 proves as exciting.

Labels: Alexandre Premat, ART, ferrari lewis hamilton, giorgio pantano, gp2, ISport, nelson piquet jr, Piquet Sports, timo glock